I crossed over the threshold into my thirties with a sigh of relief (once I’d finished my week-long panic attack between London and Ibiza.) My chaotic twenties were over and I had been promised from those that had gone before me that “Club 30” had a strict door policy and that crushing self-doubt, bad choices, limiting beliefs and uncertain relationships (with myself and others) were not on the guest list.

Instead, in would walk CLARITY and CONFIDENCE on each of my arms propping me up as I sashayed in drunk on my newfound ability to know and adore myself inside out and I for one could not fucking wait to hit that dancefloor.

But I would soon come to learn that my name wasn’t on the list either.

And nine months into the big 3-0 all the things I was told would be left behind hadn’t just remained but intensified; they were becoming stronger, louder and amid a global pandemic.

My impulse had always been to run. Literally and figuratively.

I was lucky that my multi-hyphenate career pre-corona making music, docs and podcasts took me all over the world, that I never really needed to have my feet on the ground for too long.

Which was useful because my brain wasn’t really up for taking anything slowly either.

Outside of my work I’d also spent the decade of my twenties “doing the work”; deeply embedded in spirituality and on the hunt for something more (there had to be more, right?!) Filling my free time with yoga teaching training, self-enquiry, therapy, breath-work, my first splattering of psychedelics- you name it, I’d done it.

Work. Work. Work.

And on the outset, I was #smashingit.

I had a nice life, great friends, my winning combination of empathy, artistry and justice sensitivity meant that my “success” was consistently validated externally by critics, awards and other people whose opinion I had been taught to value much more than my own. I was also by my own estimation about a maximum four stops away from enlightenment (I just needed to work a little harder…) and despite the looming coronavirus I hadn’t lost my job.

I was SO BUSY; working more than ever and had just signed a two-book deal with one of the world’s leading publishing imprints – a lifelong dream.

And yet for all the effort and the glory as 30 rolled on I felt the furthest from myself I had ever been. It was as if I was on the outside looking in, my face pressed up against the misted glass panels of the box that contained my life, straining to see it let alone live it or enjoy it. It was my twenties 2.0 only the hangovers were becoming much, much worse and this time I couldn’t run. In fact, I could only leave the house once a day because of covid. Which, dear reader, was the beginning of the end of life as I had (or hadn’t) known it.

What transpired next was a long and arduous process, the heady details of which I will share in due course across this blog, that culminated in a clinical diagnosis of ADHD.

ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) is a neurological disorder. ADHD symptoms vary by sub-type — inattentive, hyperactive, or combined — and are often more difficult to diagnose in girls and adults. It’s important to say that ADHD is not a behaviour disorder, a specific learning disability, nor it is it a mental illness (though it can and often coexists with depression and anxiety). ADHD is a developmental impairment of the brain’s self-management system.

As numbers are rising in adults and particularly in women there is a tendency from many (and its not a generalisation to say the majority are cis straight white middle-aged men) to disregard it as a “trend” or “myth” which is insulting for many reasons but especially because the reality is that women and girls do not fit the traditional diagnostic criteria which means that the complexity of our symptoms have long been ignored.

The impact of masking symptoms and overcompensating has not been considered for as long as medicine has failed us – which is, well, since forever.

It was reported in ADDitude magazine that during an interview conducted at the ADDA conference, Sari Solden who wrote “Women with Attention Deficit Disorder” said, “A significant number of women with ADHD go undiagnosed because, first of all, most women were never hyperactive and didn’t cause problems for anybody, so of course they weren’t picked up.”

Symptoms in women can be more internalised in nature with low mood and anxiety more common. Women also tend to have a lower severity of hyperactivity and impulsivity and we see greater compensatory behaviour in girls such as compliance, resilience and coping strategies. Symptoms may be exacerbated by hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy or menopause.

At various points over the course of a decade due to insomnia and burn out from my foot down in fifth-gear disposition, I was attempted to be treated for everything but ADHD. Sometimes I reconciled it as “just my artistic process”, sometimes I thought I was stupid. There were a lot of labels on shoes that never quite fit.

It wasn’t until deep into the pandemic lockdown two or three when I was living in Spain and a friend of mine who was being assessed for Autism, knowing how much I was struggling, kindly sat me down and said “I think you might have ADHD.”

Until then those letters hadn’t even been on my radar nor my doctors who shunned my eventual plea to consider a diagnosis with,“A lot of women think they have ADHD, Hana” and an exasperated sigh that confirmed my concern that literally no space was safe from the patriarchy.

“But what if they do have it?” I squeaked back, frustrated, hot tears already pooling in my eyes, now convinced by the extensive research I’d done and the social media accounts I’d starting to follow that it was highly likely that I absolutely had ADHD and no one was going to help me.

I’ll talk about how I finally got my diagnosis in another post, but safe to say, it wasn’t thanks to this particular Doctor. There’s no shade thrown there, the NHS is at breaking point and time and resources are limited while workers are beyond capacity, but a response like that does nothing to quell the stigma.

When I did finally receive my “official” diagnosis, the clarity was intoxicating. I have to say that it wasn’t enough for me to self-diagnose. That works well enough for a lot of people and if you’re one of those people and it has served you on your journey and has allowed you to make positive changes - then that’s great.

Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

I do believe that a diagnosis is very helpful especially for determining appropriate roots of behavioural management, and essential if what you require is medication and specific therapy. But i’ve also been reckoning with how much of my initial feelings around diagnosis were also wrapped in my innate capacity to seek approval and validation from others because I’ve never quite felt like I was enough.

To be clinically validated- well, fuck me.

With that I became high on relief and I was desperate to tell EVERYONE that it all suddenly made sense, that I made sense. All the disparate pieces of my puzzled brain suddenly clicked into place and I saw everything in full technicolour for the first time.

I was a bloody masterpiece!

The imagination! The empathy! The energy! The creativity! The work ethic! The artistic process! The burn out! The insomnia! The people pleasing!

It all made glorious, glorious sense.

And you bet I was donning my hero pants and sequin cape and telling the whole world that ADHD was my superpower.

Parts of my brain are totally and utterly brilliant and I now know just how important it is to remind yourself to appreciate and celebrate those parts. You’re going to need them to leverage the really challenging shit it hurls at you.

But I think in the beginning I was very naive about the complexity of my disorder and it took a while for the hangover from that potent relief to fully take hold.

In fact it was about ten months post diagnosis when one sorry night I came down hard with the crushing realisation that this was it. A diagnosis was not the silver bullet that was going to fix my problems but rather it was the can opener cutting through the lid of the worms. It wasn’t just that I had things or behaviours to overcome and conquer, no. This was how it was going to be, how I was going to be forever. I was going to have to manage this forever.

And that made me feel hopeless and very, very sad.

I would come to learn that there is a lot of grief associated with a diagnosis in later life.

My ADHD is categorised as “severe” and yet because of the coping mechanisms and masking behaviours that I have cultivated since childhood, I have also been categorised as “high functioning” though this isn’t part of the formal diagnostic criteria.

No, it was something the psychiatrist said to me along with the words “I honestly don’t know how you’ve managed this for so long.” Many patients and clinicians describe ADHD as an iceberg where most symptoms lay hiding under the surface — out of sight but ever present.

Despite being “high functioning”, my symptoms can still fluctuate in severity.

On the Occupational Therapy Report post diagnosis my thought patterns particularly around my self-esteem were described as “destructive.” For all the tools I’d unknowingly adopted to cope, I’d also spent my lifetime berating myself for not being able to do “normal things” like maths, which I failed (fuck you Sunak) or being able to sleep. I wondered for years just when and where everyone else had learnt how to do it. I later reconciled that I was just “bad” at sleep without any further questions.

I procrastinated extensively while simultaneously undertaking intense work loads and nailing them to perfection moments before deadlines were due. I really struggled to sit still on a yoga mat and just “clear my mind” for ten minutes during meditation and I needed to go for long walks ALL THE TIME. (Turns out movement IS my mediation.)

I partied too much and worked too hard in my twenties (hello dopamine and validation you heady bastards) and feeling “less than” just became my constant companion.

There was a lot of grief wrapped up in that realisation too.

It’s very easy to stay wading in the murky waters of “what if”.

What if I had been diagnosed earlier?

I did for a while and still do from time to time, it’s very human I think, to mourn what could have been. But stagnating in the past isn’t useful for anyone. It’s important to look at it though. Not pack it away in a box but fold out it out in front of you like fresh linen and face it so that you can start to clear space for things that deserve your full attention and energy like the present and the future.

Not only knowing but learning to accept what I’m dealing with has empowered me to make changes in how I live. I’ve made it my business over the last couple of years to accept, honour and forgive myself for what was and to really commit to understanding that every day, no matter what happens, I have a choice in how I show up and participate in my life.

I know that if I wake up early and go for a walk, a cold water swim and grab a yoga class i’m going to have an infinitely better day than if I just get out of bed and go straight to my laptop. Even if it’s a short walk and a cold shower on a busy day. I also know that if I haven’t slept very well, not to pass judgement on maybe staying in bed an extra hour and catching up so i’m better rested. Again, the only person determining that is me; both the action and the judgement.

The harsh critiques I had placed on myself meant that I felt disempowered, and that wasn’t a feeling I wanted to stew in any longer. I’ve learnt that whatever you are seeking in this world, you must first give it to yourself.

I needed to make self-compassion my bassline. It’s a practice that takes work but it’s crucial and I am capable. As are you. The courage of living is to try but also to fail and then try again.

Since having turned some sharp and terrifying hairpin bends with my ADHD, I’ve now found myself in an ok place with it. I’m not dancing on the ceiling, but for the most part, I’m no longer fighting against it and instead have made a commitment to understanding it and to understanding myself better.

I’ve had and continue to have a very big life and ADHD has been with me the whole time; we’re in it for life, after all. We might as well get comfortable.

Reconciling the science of the matter also allowed me to move forward.

“It’s not you babe, it’s chemical.”*

(*Technically, it’s more complicated that so to be continued, but punchy for the intro, right?!)

SO, with my white flag raised and the kind of calm that often precedes a (shit)storm, I decided that now was the time to start writing it down. Partly because I see an enormous benefit in breaking through the bullshit out there and sharing the actual lived human experience of neurodivergence and it’s always easier if someone else goes first, isn’t it?

I’m not an expert or an authority on anything but my own personal experience and I don’t want to give a false impression that everything is awesome and that I’ve nailed it; it’s a process but I have made progress. That’s important to acknowledge.

And actually, for the most part, everything IS awesome while being simultaneously challenging. The two can and do coexist.

That’s important to acknowledge too.

Some days are REALLY great, some days are unremarkable and some days I’m still afraid of my brain. I want to use this space to talk about all those days.

I often say that shame and stigma are isolating little bastards so I want to raise awareness as much as I am able to, to try and dispel some of that. I'm not ashamed of my ADHD, far from it. I wear it proudly; the good, the bad and the ugly, because it is all of those things, and to pretend otherwise would be to do ourselves a disservice.

Life is so rich in complexity, in difficulty, in beauty, it's the best and the worst of us.

And that is something I really wanted to make space for here, the juxtapositions that ultimately make us human; the chaos and the calm, the ordinary and the fucking iconic, the guts and the glory.

We always give to the world what we need the most.

Being honest about the reality of being neurodivergent has also enabled me to start to cultivate a community. Finding and connecting to people that are also grappling with a late diagnosis. I have always believed that talking and being listened to, and I mean really listened to, are as fundamental for our survival as an inhale of air.

Its deeply humbling to realise that the things that once made you different or perceived as difficult can be quite common and at the same time despite those commonalities, we are all grappling with brains as unique as we are. For all the struggles, I still think that’s pretty cool.

Like with any spectrum-based disorder where the type and severity can vary widely, nuance is essential and something I’ve felt lacking in the current discourse on ADHD in particular.

There are so many things to consider, and I’ll admit I’ve felt cautious; over the last year I’ve kept a careful eye on the number of white, “successful”, creative women who are discussing their own diagnosis and wondering how useful it is to add my take to an already saturated conversation.

Then there is the influx of coaches, experts and consultants that have popped up with a diagnosis but no qualifications, while ADHD and other disorders and their symptoms are being oversimplified for the sake of punchy infographics on Instagram (guilty) or short videos on Tik Tok (not guilty I’m 33.5… though we’ve still got time and lord knows I’m prone to a millennial crisis...see the great eyebrow massacre of the 90’s.)

But it's also important to acknowledge that adults, and especially women and marginalised groups have been excluded for so long and only now does it feel like we have a voice due to the amount of people coming forward in large part thanks to social media.

Medicine has failed us, workplaces and traditional educational institutions often don’t accommodate us and tabloids and Tories are hellbent on diminishing us with dangerous and factually inaccurate articles appearing daily that are only ever written from the narrow minds of those on the outside peering (and sneering) in.

But I’m not going to give those arseholes any more of my word count.

Instead, I want to take back a bit of control over the narrative, over OUR narrative and I figured that the more people that talk about it openly and thoughtfully, the more likely it is that changes can be made, societally, collectively but mostly for the individual.

For the people whose daily lives are impaired by symptoms but who have no real tools or support for coping because they simply have never had the language or a reference for what they’re feeling or why they’re behaving a certain way.

Without proper acknowledgment and management of these behaviours and emotions, so many problems can occur that decrease the quality of a person’s life, that can include and isn’t limited to alcoholism, depression, drug abuse and suicide.

25% of adults being treated for alcohol and substance use disorders are diagnosed with ADHD. Depression is nearly three times more prevalent among adults with ADHD. Adults with ADHD are also 5 times more likely than those without to have attempted suicide (14% vs 2.7%). That rises to one in four for women with ADHD.

We also need to take into account that this isn’t the same for everyone.

I had a great conversation recently with Emma Case who founded Women Beyond the Box . She said to me “I’m able to use my “ADHD superpowers” because I’m privileged. Because I can afford to have someone help me with the things I struggle with.” And I do recognise that the privilege of diagnosis is one thing, but living and thriving with neurodiversity can feel to many like an even more exclusive club.

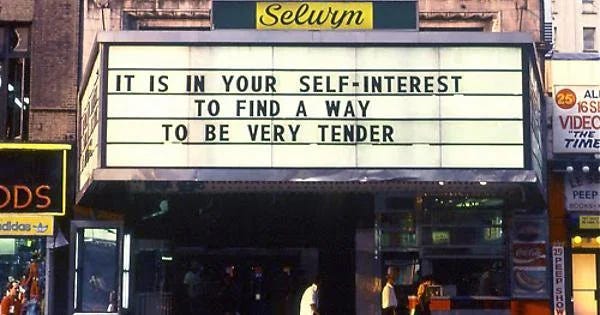

Why am I desperately trying to bargain my way into a party that rejects, dismisses or invalidates my experience of the world when I could just step back gracefully and create my own?

As well as offering posts about my own experience, it was important to me to collect and share the experiences of other adults who are also navigating being diagnosed as neurodivergent as well as scientists, psychiatrists, and researchers through written interviews and (soon) a brand-new podcast.

While I’m not going to provide a definitive “how to”, I hope in sharing these experiences I can maybe example a path forward that might give others the courage or inspiration to start to take the steps to find their own way through.

Someone said to me recently that we always give to the world what we need the most.

I want this substack to be a space of exploration and understanding around neurodiversity and all its grey areas, not as something to other, resolve or apologise for but to accept and embrace in all its forms. Now I can walk into the party with clarity and confidence, because I’m throwing my own.

As I was preparing to post this, yet another article appeared diminishing the ADHD experience. I decided to protect my peace and not read it. Instead, I opened my instagram app and the first post I saw was a quote by Shannon Mullen O’Keefe on the On Being page that I want to leave you with.

“Our future beckons us to reimagine things. It encourages us to turn our faces away from the usual and toward each other.”

My hope is that we can look to each other for support, to come together to motivate people to advocate for their own health, to give family and friends the confidence to initiate conversations about neurodiversity and to own our stories and speak for ourselves.

And perhaps by doing that we may just start to turn the dial on a conversation that continuously debates the validity of our existence while we gate-crash a world that wasn’t designed for us, but that we are boldly navigating none the less.

Worth a shot at least, eh?

Welcome to the party x

I’ve recently appeared on the brilliant The ADHD Adults podcast, where Alex and James (in)expertly cover issues around ADHD in adults, sharing evidence-based information and personal experiences.

My next post features an interview with Iman Gatti; a certified grief recovery specialist, transformational speaker and bestselling author. She works with people to help them recover from grief and trauma, elevate their self-esteem, deepen their authenticity and in her own words “step fully into the greatness they were born for.” At 39 years old Iman was diagnosed with ADHD but later learnt she had been secretly diagnosed decades early.

"I think the world is so neurotypical friendly and so the rest of us are constantly feeling ‘less than’ because most of those systems don’t consider us or benefit our brains."

- Iman Gatti

I’ll be releasing new posts twice a month. Subscribe for free so you don’t miss a post and to be the first to hear about the podcast which features some incredible neurodiverse people from across the globe.

I’m not putting this account behind a paywall because I want it to be available to everybody. But you can support this substack by sharing it!

Oh Hana. This is such an empowering post, and so beautifully articulated. Thank you for sharing. I was diagnosed with combined ADHD at 26 last year and in turbulent circumstances. I have been carrying so much shame about who I am? Who I missed out on being? I am a people pleaser, heart on my sleeve wearer, passionate and impulsive. I also crave routine but that feels like prison. I am spending a lot of time re-framing this language around myself. But because I’ve done it once I assume that’s it. That’s not the case obviously. I have always been validated by my creative processes and successes. If people like my art they must like me right? Wrong. The world is not as black and white as that. I’ve always used my art as a tool for communication and exploring the grey area. I’ve been told recently when I tried to articulate my struggles and reasons behind not being able to do certain things and they were called excuses. Negative criticism hits differently I feel with my brain. I feel it physically and it becomes the truth. Thank you so much for holding space for important conversations and helping me feel seen when I feel like I had began to lose myself.

Thank you Hana! I found your Substack through your appearance on the ADHD Adult podcast.